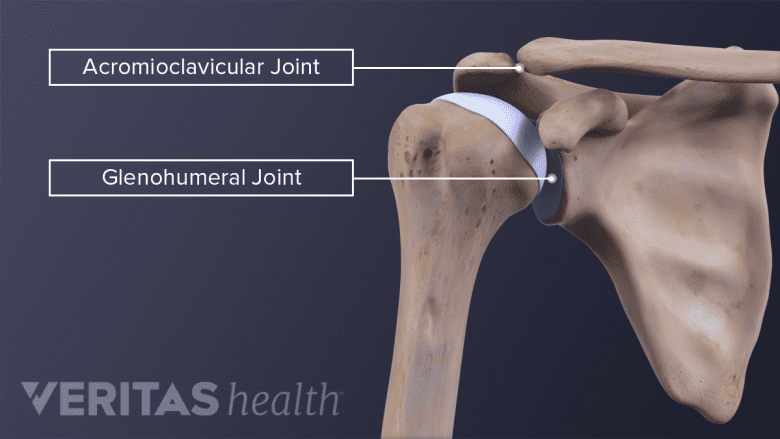

The shoulder is a complex piece of anatomy that includes four joints where the humerus (upper arm), scapula (shoulder blade), and clavicle (collarbone) meet. Two of those joints, the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints, are particularly susceptible to pain caused by arthritis.

The acromioclavicular joint raises the arm and the glenohumeral joint allows for circular movement.

- The acromioclavicular joint (AC Joint) is located where the clavicle glides along the acromion, which is at the highest point of the scapula. While the clavicle and acromion do not move a lot in relation to one another, the acromioclavicular joint facilitates raising the arm up over the head.

- The glenohumeral joint is where the head of the humerus nestles into a shallow socket of the scapula called the glenoid. This ball-and-socket construction allows for circular movement of the arm and is credited for the shoulder’s extreme flexibility.

Strong, slippery articular cartilage lines the surface of the shoulder bones at the areas where they meet. The cartilage helps the bones glide against each other and acts as a buffer to protect the bones from impacting one another. The articular cartilage is naturally thinner in the shoulder joints than in weight-bearing joints such as the knee and hips.

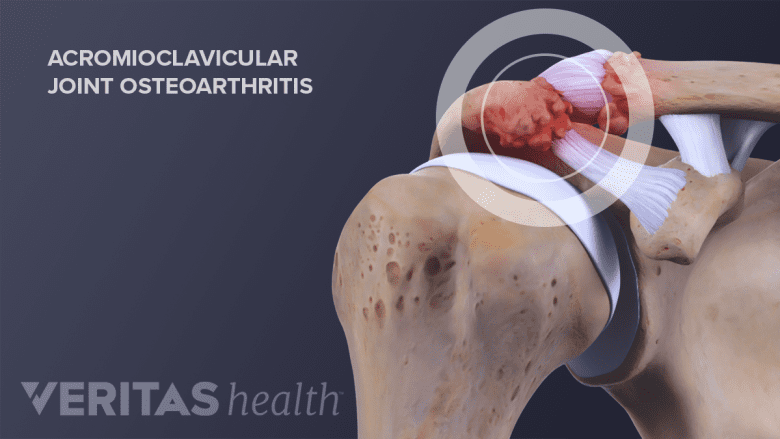

How Acromioclavicular Arthritis Causes Pain

As acromioclavicular joint osteoarthritis occurs, the cartilage deteriorates, and the joint space decreases.

The arthritic process begins with deteriorating cartilage, which may be frayed, bumpy, thin or even missing in some spots. In the acromioclavicular joint, the following process may ensue:

- The cartilage deterioration reduces the space between the scapula’s acromion and the end of the clavicle, the two bones that form the AC joint. As this joint space decreases, there is friction between the acromion and the clavicle.

- To compensate for the deteriorated or missing cartilage, the bones in the joint may produce small scalloped growths called osteophytes, or bone spurs. In turn, the bone spurs can create even more friction in the shoulder joints.

It is important to note that cartilage does not contain nerves, so damaged cartilage is not the primary source of pain in AC joint osteoarthritis. Likewise, bone spurs are a normal sign of aging and the presence of bone spurs alone are not a cause for concern.

However, the friction between bones and other resulting abnormalities in the shoulder can cause discomfort and pain. For example, as cartilage in the acromion joint deteriorates, the joint space shrinks and tendons can be impinged, resulting in tendinitis.